In the Near Future Do You See Yourself as a Consumer Producer or Prosumer of Digital Arts

Abstract

Since the First Industrial Revolution, consumers accept been mainly considered as playing a passive role with regard to product. However, the recent decades take seen a progressive growth in consumer interest in production processes, for instance, in the form of user innovation, DIY and mass customisation. Nevertheless, information technology was non until the advent of digital technologies that consumers' input in production processes could go really significant in all dimensions of product (design, manufacturing and distribution). This increased (sometimes leading) role of consumers in production has been referred to as 'prosumption'. While prosumption has and so far been mainly meaning online (where consumers take arguably taken over the creation and distribution of content), recent advances in digital technologies (mobile networks, 3D printing) accept enabled prosumption to reach to globe of physical objects, as illustrated by the increased importance of consumer-made appurtenances ('makers' motility) and of the 'sharing economy'. Although prosumption can exist highly disruptive to markets, there has not been so far a thorough investigation of the nature of this phenomenon. Yet, understanding this nature is critical to apprehend disruptions. Furthermore, while digital technologies have been acknowledged as a key factor in the ascent of prosumption, the exact role of each set up of technologies has not still been studied, which is a problem, as different technologies enable dissimilar types of prosumption. The aim of this commodity is to fill these ii gaps. To do then, a framework of prosumption, which encompasses both inputs and outputs of consumer contribution, is introduced. This framework is then applied to multiple case studies, which enables to show how prosumption has evolved and what changes lie alee.

Introduction

As a form of Open Innovation, User Innovation has had a growing importance over the past few decades, both in the literature and as a office of firms' strategies. While firms accept always used to some extent user input every bit a source of innovation (Rayna and Striukova 2010), the concepts of 'User Innovation' and 'Lead Users' take gained a widespread acceptance following the seminal works of Eric von Hippel (von Hippel 1976, 1977, 1978, 1986). Yet, both in these works and in the arable literature on User Innovation that has ensued, user input is generally only considered at the conception stage. Regardless of how inventive they are, users are seen as jump to the firm, because they lack the manufacturing, distribution and commercialisation capabilities that only firms accept.

While this might have indeed been the instance until the belatedly 1990s, the progressive improvidence of digital technologies (in particular, following the Net 'boom' of the mid 1990s) has radically and durably changed the human relationship between users and firms. Indeed, a mutual trait of all digital technologies is that that they empower users, and in item consumers, with the power to create, replicate, distribute and (in some instances) commercialise (Rayna 2008).

The wide availability of digital technologies means that user innovation is no longer restricted to professional end-users and, indeed, consumers accept been increasingly engaged in co-creation activities with firms (Rayna and Striukova 2015). In fact, looking at the massive quantity of User Generated Content available online, one could even argue that consumers have in some cases superseded firms, as they now play a leading part in design, 'manufacturing' and distribution.

As a consequence of their increasingly agile function in the production processes, consumers have progressively become 'prosumers'. Since innovative users are no longer bound to the firms, countless user innovations have taken place independently from the firms and, sometimes, even confronting the firms' will (Zwass 2010; Rayna and Striukova 2015). Every bit a affair of fact, whether legitimately or not, the number of cases where consumers straight compete with firms (for instance by diffusing innovations that accept been rejected by the firm) has sharply increased over the by few years. Footnote i Hence, as a consequence of the diffusion of digital technologies, the relationship betwixt firms and users has turned from simple cooperation to (potential) coopetition.

While coopetition between prosumers and firms only used to be prevalent online, the recent advances in digital technologies have led this phenomenon to spread to the rest of the economy. For case, digital manufacturing technologies, such equally 3D printing and condiment manufacturing, provide end-users (and progressively consumers) with the ability to manufacture objects. In fact, in that location have already been numerous cases of users manufacturing and selling improved versions of existing commercial products or items complementing such products. Footnote 2 Such technologies have even given rise to consumer-borne ecosystems around popular products (e.g. Legos, Star Wars). Besides manufacturing, contempo advances in digital technologies have as well began to considerably disrupt the service industries (e.k. taxis, vacation rentals), with prosumers starting to supply services in direct competition with businesses, by renting out their cars (or driving people around), their flats, their expertise, or whatever other asset they might own; the inescapable 'sharing economy' is indeed yet another form of prosumption.

As the prosumer phenomenon is arguably spreading to the whole economy, information technology is critical to sympathize meliorate the roots and development of this phenomenon. To do and so, 1 has to consider how, and to which extent, digital technologies accept given means to consumers to contribute to product processes, and whether such contributions are related to pattern (when user innovation traditionally takes identify), manufacturing or distribution.

To practise so, this article introduces an 'input-output' prosumption framework that enables to analyse consumers' involvement in the production procedure with regard to both the type of input they contribute and the type of contribution (relative to the production process) that is fabricated ('Towards a prosumption framework' section). Then, based on multiple case studies and using a historical arroyo, this prosumption framework is used to investigate the evolution of the impact of digital technologies on prosumption and user innovation: Sect. 3 discusses user innovation and prosumption in the pre-digital era; Sect. 4 investigates user innovation and prosumption in the early (mid 1990s-mid 2000s) digital era; Sect. 5 studies the impact of Web 2.0 (due east.g. social media) technologies on prosumption and user innovation; and Sect. 6 considers the most recent impacts of digital technologies and explores the consequences of user manufacturing (through 3D printers) and of the sharing economy. Finally, Sect. 7 tackles the upshot of leveraging prosumption from a firm'south perceptive and outlines related good practices.

Towards a prosumption framework

While the give-and-take 'consumer' appeared in the English language some fourth dimension during the late Centre Ages, Footnote 3 the modernistic concept of consumer every bit someone who purchases goods and services for personal utilise unsurprisingly came into beingness in the late eighteenth century, at the time of the First Industrial Revolution. Indeed, mechanisation, and the resulting concentration of means of production information technology necessarily entailed, meant that for the showtime time in history, production and consumption of goods and services became largely asunder. Footnote iv

From then on, the perception of the importance of the office played past consumers in the economy progressively grew, up to a point where later Earth War 2 consumption started to be considered as the focal point and driving strength of modern economies, which had by then become 'mass consumption societies' (Matsuyama 2002). Withal, while recognised every bit critically important, the part of consumers was still seen as essentially passive, and even increasingly so, as both consumption choices and volumes of consumption were thought to exist triggered by corporations, through ad (Galbraith 1958, 1967).

Hence, the traditional view of mass consumption lodge is that firms are in charge of deciding, designing, manufacturing (producing), marketing and distributing appurtenances and services, while the part of consumers is, plainly, to consume. Yet, this ultra-passive view of consumers began progressively to change in the late 1970s because of the success of 'new' business models, which involved some degree of consumer participation (e.thousand. fast-food restaurants, flat packed article of furniture).

Taking notice the increasing office of consumers in the production processes through DIY ('do-information technology-yourself') activities (such as self-service, cocky-assist and self-repair), Toffler (1981) coined the term prosumer, a portmanteau word of 'producer' and consumer. Besides the consumer interest in production processes through DIY activities (which was already happening at the fourth dimension), Toffler (1981), considering advances in calculating, as well foresaw a consumer involvement of in the design of customised products (admitting to a fairly minor extent, i.e. providing measurement for customised clothing or objects). Kotler (1986) developed this thought further and emphasised that progresses in information and communication technologies would presently enable consumers to creatively engage in production processes, through mass customisation (i.east. choosing amongst a range—ofttimes broad—of options gear up by the producers, who then manufacture the products on demand).

While 'DIY' business models certainly picked up during the 1980s, with more firms integrating self-service into their products (e.g. factory outlets, abode repairs), it took over 3 decades for the mass customisation foreseen past both Toffler (1981) and Kotler (1986) to take identify at a meaning calibration. Consequently, information technology is not surprising that, for a while, the prosumer concept seemed all but forgotten in the literature. Footnote 5 Even so, this concept began to regain popularity during the 2000s, following the appearance of Web two.0 technologies (and, more specifically, social media) in particular.

As noted in Rayna and Striukova (2015), Web 2.0 technologies enable consumers to contribute and share textual and multimedia content over the Internet, with about no technical knowledge beingness required. Services such equally Facebook, Flickr, YouTube, and Wikipedia, led to a surge of consumer (or user)-generated content bachelor online. As highlighted in Tapscott and Williams (2006) and Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010), it became rapidly clear that in all these services, consumers, and non firms, were actually doing the 'bulk of the work'. Indeed, as noted in Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010):

Prosumption was clearly not invented on Web ii.0, only given the massive involvement in, and popularity of, many of these developments (e.g. social networking sites), it can exist argued that it is currently both the most prevalent location of prosumption and its most of import facilitator equally a 'means of prosumption'.

Nonetheless, as volition be shown in the post-obit sections, prosumption is nowadays far from existence restricted to online content and technologies, such every bit 3D printing and smart electricity grid, accept enabled consumers to engage in the product (in the sense of manufacturing) of physical products.

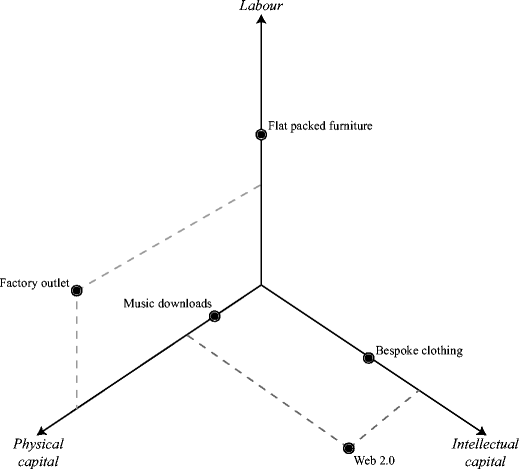

Looking at the literature, it is clear that prosumption tin can have many different forms, some complex, other much simpler. To fully apprehend this phenomenon, it is thus critical to be able to categorise prosumption activities. Withal, when doing then, a further difficulty arises because two unlike aspects have to exist considered: (1) what the nature of what is contributed past the consumers to the production process is and (ii) to which aspect of the production process it is contributed. Hence, the prosumption framework introduced in this article consists of two taxonomies: ane related to the prosumption inputs in the production process (Fig. 1), and the other related to its output (Fig. 2).

Taxonomy of prosumer input in the product process

Taxonomy of prosumer output in the production process

With regard to inputs, a thorough exam of the various cases of prosumption activities shows that consumers either provide labour (in the sense of work force, as in the case of flat packed furniture), intellectual uppercase (for those activities where consumer creativity and expertise are required; for instance, customisation), or physical capital (in the case where consumers' ain physical assets are used every bit a role of the production process). Interestingly, some prosumption activities require consumers to combine several types of input. For case, mill outlets require the consumer to provide labour (i.e. to carry the goods), but too to accept (or rent) a car (concrete capital). Likewise, contributing to Web 2.0/social media requires both knowledge and inventiveness (intellectual capital), but also to take an Cyberspace connected device or computer (physical capital).

Are at that place prosumption activities that require all three types of inputs? Indeed, there are. For instance, this is typically the case for user innovation when information technology relates to concrete goods. User innovation requires consumers to provide intellectual capital. Consumers engaging in user innovation as well demand to take tools (physical capital), and building a epitome may also require difficult labour, as no machinery is bachelor at prototyping stage. Footnote 6

Information technology could exist argued that when consumers accept role in production processes, they either contribute 'time' or 'money' (or a mix of both). This is actually reflected in the taxonomy presented in Fig. 1. Indeed, the two axes, labour and intellectual capital, correspond to a contribution related to time (whether 'force' or 'brains'), whereas the 3rd axe, physical majuscule, relates to money. In this respect, information technology can be noted that, indeed, in many cases, prosumers confront a trade-off between providing time and money (for instance, a wealthier prosumer could pay someone to mount flat packed piece of furniture, whereas a less wealthy prosumer engaging in user innovation would probably build a prototype by hand instead of using a 3D printer). Footnote seven

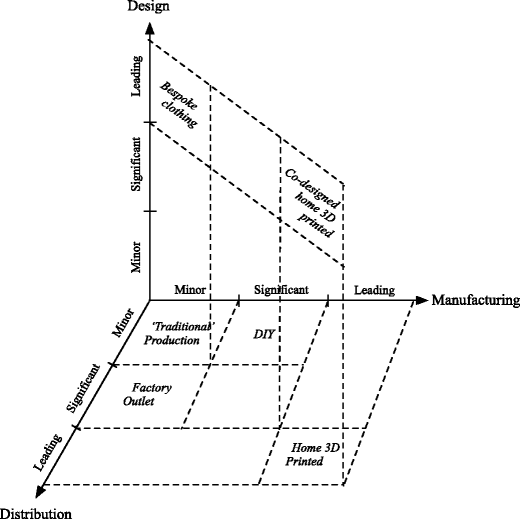

Equally shown in the output taxonomy (Fig. 2), the inputs provided by prosumers can contribute to unlike parts of the production process. Indeed, prosumers can contribute to design (in its broadest sense, i.east. all that pertains to the conception stage of a product or service), manufacturing (understood here every bit the reproduction, whether tangible or intangible, of a product or service) and distribution.

Whereas 'traditional' production usually involves fairly petty participation from the consumers (i.due east. no participation in design, no or fairly little associates required, involvement in distribution is limited to visiting a local store), other forms of product entail a more significant contribution (Fig. 2). Manufactory outlets, for instance, require a meaning involvement of consumers in distribution, since they need to drive (presumably) further to the factory instead of going to a nearby store. Likewise, DIY (e.thousand. flat packed furniture) requires consumers to contribute to manufacturing, as they acquit out the terminal associates of the product. Finally, mass customisation leads to consumers playing a role in pattern, a function that can range from minor to significant, depending on the number of customisation options offered and the extent of the modification of the product. In some cases (e.g. bespoke habiliment), considering customisation options bachelor are not prepare (and possibilities are 'endless'), consumers can even take a leading role in pattern.

While many examples take been given in the literature, there is currently no clear definition of what prosumption really is. This is certainly due to the fact that prosumption can take very different forms. Thus, the output taxonomy in Fig. 2 enables to ameliorate define what prosumption is.

In the literature, prosumption is considered as a state of affairs where consumers accept an active role in productive processes. Yet, even in the nearly traditional and 'passive' view of consumption, consumers accept always played an agile role, albeit a pocket-sized one, in distribution (e.g. going to the store) and, to an even lesser extent, in manufacturing (e.g. unpacking the product, putting batteries in an electronic device). Thus, based on the taxonomy in Fig. 2, prosumption tin can be defined as follows:

Suggestion i

Prosumption is defined as a situation where consumers are involved in productive processes in either of the following ways:

-

Consumers are involved to any extent in design.

-

Consumers are involved significantly in manufacturing.

-

Consumers are involved significantly in distribution.

User innovation is divers in von Hippel (1976) as a situation where users have a leading office at the design stage of a product (or service). Users perceive the need for an innovation, which leads to an invention. Users then build and test a prototype, which is and so commercialised (if successful) past the company. Looking at Proffer one, it is clear that this definition corresponds very well to 1 detail case of prosumption: when consumers are (heavily) involved in design, but not significantly in manufacturing and distribution.

Thus, when carried out by consumers (there are, of course, cases when user innovators are not consumers), user innovation is, in fact, a component of prosumption. Footnote eight

Proposition two

User innovation, when carried out by consumers (i.e. for final consumption purpose), is a form of prosumption related to the design stage of the productive process. In such a case, user innovators are prosumers.

The two frameworks (Figs. 1 and 2) and the two propositions introduced in this department volition be used in the following sections to analyse the impact of digital technologies on prosumption and user innovation.

Prosumption in the pre-digital era

Prosumption in the pre-digital era has been largely touched upon in the previous department. Examples drawn from the literature, in detail Toffler (1981), Kotler (1986) and von Hippel (1976), every bit well every bit the related prosumer inputs and outputs they entail, are summarised in Table ane. Looking at these examples, information technology is clear that they are rather unidimensional, both from the input and the output perspective. The only exception is user innovation, equally in the pre-digital era, it generally involved all three types of input.

Indeed, innovating consumers had non only to remember but likewise to carve, solder, cut, etc. with their ain tools in order to build a epitome. For instance, when mountain biking began in the early on 1970s, existing commercial bikes were not suited to this blazon usage. As a event, early users created their own bikes out of strong onetime bicycle frames (or built new frames by soldering thicker tubes), with airship tires and motorcycle lever-operated drum brakes (Lüthje et al. 2005). They were therefore using their blueprint (intellectual capital), spare parts and tools (physical majuscule), as well as labour.

However, the relative level of contribution related to each type of input did essentially depend on the case at hand (for instance, building the paradigm might require a significant amount of intellectual capital but footling labour or investment in tools). With regard to output, user innovators were in some cases leading the evolution of new products, while in other cases, they only made fairly minor contributions to design. In all cases, however, pre-digital user innovation was on the output side virtually ever restricted to design, as users had no means to manufacture (on a big scale) and distribute their innovation and, therefore, had to rely on companies to do so.

Prosumption in the early digital era

For most consumers in the 'more than economically adult countries', the early digital era spanned from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. In the mid-1990s, the Internet, but also other forms of digital replication and distribution (e.g. CD/DVD burners), started to become widely available. Nonetheless, equally opposed to the Spider web ii.0 era that ensued, the early digital era was still characterised by rather passive consumption (e.g. consumer would subscribe and read online the encyclopaedia Microsoft Encarta), as the tools enabling to create and distribute digital appurtenances, while available, were rather difficult and tedious to use. Footnote 9

Every bit a matter of fact, in the early function of this digital era, it is even rather hard to observe whatever significant example of prosumption. This began to change in the late 1990s, first with the advent of peer-to-peer network technologies, and then with the availability of (legal) digital downloads.

Interestingly, information technology is a (consumer) user innovation that unleashed the first wave of digital prosumption. Frustrated past the lack of instant music download (dorsum then, buying music online meant receiving a CD by the mail a couple of days afterward you lot ordered it) and taking reward of the newly released 'MP3' audio compression format, three college teenagers, Shawn Fanning, John Fanning and Sean Parker, developed and released the get-go largely adopted peer-to-peer network. Napster, which enabled consumers to hands share and download music files from ane some other, became an instant and massive success. Within a matter of months, Napster reached lxxx million users, who arguably set upwardly the start (albeit non-commercial and not-IP compliant) online music distribution service (Gowan 2012). Footnote 10

While Napster was close down by court order in July 2001 after 2 years of functioning, other peer-to-peer sharing protocols (e.grand. Kazaa, eMule, BitTorrent), also borne by big user communities, chop-chop emerged. Dissimilar Napster, which was restricted to music files, these new protocols could be used to share any kind of digital media (e.g. movies, software, books, pictures) and were far more resilient to court orders.

The rapid emergence and diffusion of the peer-to-peer sharing protocols, carried out in total independence from the industry (and in spite of information technology), are hallmarks of the impact of digital technologies on user innovation. Unlike in the example of pre-digital user innovation (Table i), digital technologies enable users to replicate (manufacture) and distribute digital goods without the help of any firm. Quite strikingly, the first meaning user innovation of the digital era has been to provide tools (peer-to-peer networking protocols) enabling consumers to independently (and in a totally decentralised manner) replicate and distribute digital goods amidst themselves (whereas, until and so, they had to rely on key servers owned past companies).

A couple of years afterwards peer-to-peer networks emerged, the manufacture, finally perceiving the needs for a legal offer of digital content, began to supply music, films, Tv shows, and software over the Net. This new fashion of content commitment made consumers de facto prosumers. Indeed, unlike before, when the goods (e.g. CDs, DVDs), even if ordered online, were manufactured and distributed past the firms (sometimes to the consumer's very door), online digital commitment (whether download or streaming) necessarily ways that consumers have part in both manufacturing and distribution. Indeed, their Net bandwidth is used to 'transport' the goods and their hard drive (or other storage media) to 'fabricate' and store the goods.

Tabular array 2 summarises, with regard to both inputs and output, the iii new modes of prosumption enabled by the appearance of digital technologies. In item, in relation to user innovation—'Napster (software)'—the difference with pre-digital user innovation (Table 1) is striking. The (legal) 'Music Downloads' example shows new mode of consumption where prosumption becomes the norm and where consumers play a significant function in manufacturing and distribution. However, as illustrated past the 'Napster (usage)' example, firms are no longer necessary. In the case of peer-to-peer networks (which are used for both illegal and legal content), prosumers tin fifty-fifty play a leading role and completely bypass traditional manufacturing and distribution channels. Footnote 11

Prosumption in the Web 2.0 era

Hence, digital technologies have transformed consumers into prosumers for digital appurtenances. Yet, in the early years of the digital era, prosumption was mainly restricted to manufacturing (in the sense of reproduction) and distribution, because the tools enabling to 'design' (create) digital content were still expensive and rather circuitous to operate (a legitimately caused software suite enabling to publish content online would range from around hundred of euros to a couple of thousands).

This inverse significantly in the mid-2000s with the advent of Web 2.0 technologies. Unlike their forebears, Web two.0 online services were such that about no boosted tool was required to create and publish content online. Whether social media (Facebook, Twitter), content sharing platforms (YouTube, Instagram, Flickr), information assemblage and sharing (Wikipedia), these platforms 'moved' the tools of creation from the desktop computers to the Web, thereby making them gratuitous of access and much easier to use (circuitous software could simply not be deployed online, so it had to be simplified and only retain essential features).

As noted in Rayna and Striukova (2015), Web 2.0 technologies have considerably lowered the barriers to user creation and, in fact, many Spider web 2.0 services derive their value nearly exclusively from the content created by users. Yet, while the 'early on digital era', discussed in the previous section, was characterised by consumers taking a leading role in manufacturing and distribution, the 'modern' digital era is significantly different. Indeed, far from taking reward of the prosumption potential provided to consumers past digital technologies, all Spider web 2.0 services have adopted a central way of distribution. Of course, consumers however contribute (they demand an Internet continued device to consume), but this contribution is far smaller than what could have been washed if social media or Wikipedia, for instance, had been hosted on a fully decentralised consumer network.

While this may seem a fairly small-scale result, this is a clear example of a deliberate determination not to accept advantage of prosumption capabilities. As a issue of this conclusion, consumers in many countries accept been experiencing Cyberspace bandwidth problems, because anybody is pulling digital content from a handful of centralised servers. Alas, overcoming this problem requires significant investment: When thousands or millions are watching the same high-definition YouTube video hosted on centralised servers, the bandwidth needed is simply enormous. Yet, at the same fourth dimension, all these consumers make piddling (if whatever) use of their upstream bandwidth, which could be used to share with other consumers the bits of the video that take already been downloaded. This would certainly be a much more efficient and a far less costly manner to distribute videos.

This is something that the British BBC understood perfectly well when information technology launched iPlayer, its Internet streaming grab-up television and radio service, late 2007. Daunted by the enormous investment required to host such a service using centralised servers, BBC decided instead to develop its own peer-to-peer network as the backbone of iPlayer. Hence, when watching a replay of a BBC programme, consumers would, at the same time, share this video with other consumers willing to scout information technology. Videos were of course encrypted using a Digital Rights Management (DRM) system, so that users, fifty-fifty though they were distributing the videos, could not salve them on their difficult drive or share them outside of the iPlayer service. Unfortunately, because of the bad reputation of peer-to-peer networks (irremediably associated with consumers piracy), and despite not a single case of IP infringement taking place with iPlayer, BBC removed this feature late 2008 and moved on to a less efficient (and more plush) centralised way of distribution.

Tabular array iii illustrates the respective prosumers' contributions for these 3 cases. In the case of social media, the matter is notwithstanding slightly more complex. Indeed, while consumers do not physically take part in reproduction (manufacturing) and distribution of content, which is hosted on the companies' servers, they practise play a leading office with regard to which content is ultimately consumed (and distributed). Indeed, the more a particular content is 'liked' or shared, the more than it is viewed and distributed. Hence, 1 could consider that, in spite of the centralised hosting, consumers play a leading role, with regard to manufacturing and distribution on social media.

Comparison Tables 2 and three, one can discover not only a relative 'decrease' in prosumption related to manufacturing and distribution but also greater levels of prosumption at the pattern stage. In fact, the table could have been filed with examples of online platforms where consumers essentially produce most of the content. Of course, this does not mean that there are no other forms of prosumption, as the BBC example shows. Yet, while technically possible, information technology does non announced that there are, as nevertheless, examples of (legal) prosumption where consumers are leading with regard to all 3 aspects of the output.

Prosumption goes offline: 3D printing and sharing economic system

Until recently, and bated from the handful of special cases presented in 'Prosumption in the pre-digital era' section, prosumption was largely idea to be mainly an online miracle. Nevertheless, present, prosumption increasingly also happens 'offline'.

1 of the reasons for that is the advent of digital manufacturing technologies, such every bit Additive Manufacturing/3D printing. While these technologies take at present existed for a couple of decades, their very high price (generally tens or hundreds of thousands of euros) has kept them out of hands of consumers. However, the cost of 3D printers has quickly decreased over the past few years (prices have been cut tenfold in just 5 years). Nowadays, domicile 3D printers tin can be purchased for less than a grand euros and professional-form printers for less than 2500 euros (Rayna and Striukova 2016).

These new manufacturing technologies enable consumers to take a leading part of both manufacturing and distribution of physical objects, and in that location are already countless of examples of prosumption activities that take been enabled by 3D printing technologies. One of such cases is the Square Helper.

Chris Milnes, creator of Square Helper, noticed during his 'consumption activities' an issue with the Square smartphone bank card reader that an increasing number of java shops and food carts in his neighbourhood were using. When the employees would attempt to swipe the card, the Square carte du jour reader (connected to the jack audio plug of the smartphone) would spin, preventing the card'south magnetic strip to be read correctly and even potentially damaging the card (Martin 2013). Frustrated past the extra waiting fourth dimension when paying considering of this flaw in the card reader blueprint, Chris Milnes decided to pattern and build a prototype of a widget that placed between the smartphone and the reader, which would prevent the latter from swivelling.

This looks, and then far, like a typical case of prosumption related to user/consumer innovation. Where it gets interesting is that the appearance of digital manufacturing technologies has provided this prosumer with manufacturing capabilities. Before the advent of (inexpensive) 3D printing, prosumers like Chris Milnes would have had no choice just to find a company to manufacture his widget (about likely, in the instance of Chris Milnes, he would accept contacted the visitor that makes the Square reader, hopping for his innovation to exist integrated in the product line, which it may have not).

Digital manufacturing technologies considerably increase consumers' prosumption capabilities and, instead, Chris Milnes purchased a 3D printer and started to manufacture his widget (which he named 'Square Helper') at home (he calculated that he could build up to 700 U a week), built a uncomplicated website with a PayPal shopping cart and started to sell and distribute the widget himself. Footnote 12

Nonetheless, this kind of 'total-range' prosumption, where consumers are leading in all inputs and outputs, does not necessarily require domicile manufacturing, as the latter may also be outsourced (simply like a firm would). For instance, a consumer (wishing to remain anonymous, but going by the alias 'Autoparis and Me'), user of the Autolib' French car sharing service, got frustrated by the lack of docking station in the machine enabling him to use his telephone as navigator. This consumer built a prototype, specifically designed for the Autolib' car (the dock clips to the dashboard vents of the automobile). Once this was done, he uploaded the digital blueprint of the dock he designed on two online 3D printing platforms (Shapeways and Sculpteo), where he outsources the manufacturing and distribution. When someone purchases the smartphone dock on either platform, the dock is then 3D printed on demand by the platform, and then packaged and shipped by the platform to the customer. Footnote 13 , Footnote 14

There are also cases when prosumers outsource the 3D printing manufacturing of physical products they have designed, but exercise the distribution themselves (for instance, because they wish to include a manual or other complementary items). In all cases, however, when consumers outsource both manufacturing and distribution, this is still prosumption, because consumers are leading manufacturing and distribution (albeit by commission), merely like a regular producer would.

The impact of these new digital manufacturing technologies is, however, non limited to the user innovation cases presented to a higher place. Indeed, 3D press technologies besides empower consumer to provide services to other consumers (or fifty-fifty firms). 3D Hubs is a perfect instance of that. This online platform enables people who would similar to 3D print and do not accept a printer to find people around them who have 3D printers and are willing to print for them for a fee. At this time, over 23,500 'providers' have signed up with 3D Hubs. While some of these providers are professionals equipped with very expensive machines, the vast majority of them are individuals (oftentimes arts, design and architecture students, besides as hobbyists) who use the service either to recover the cost of the printer or to supplement their income. 3D Hubs is, in fact, a direct competitor to the leading online 3D printing platforms, such as Shapeways, Sculpteo or i.Materialise (Rayna et al. 2015), and information technology is a clear example of prosumption where consumers are leading with regard to manufacturing, only also provide the key input (physical capital).

This last example, where owners of 3D printers 'share' (for a fee) their spare chapters with other users, is, in fact, quite reminiscent of what is generally referred to every bit the sharing economy. Also, occasionally chosen 'collaborative economy', this concept encompasses platforms, such as Airbnb, Footnote 15 Blablacar, Footnote sixteen Uber, Footnote 17 which enable users (more often than not consumers) to rent out something they own or provide services to each other.

As emphasised in Belk (2014) and Hamari et al. (2015), it is the ascent of digital technologies (in particular ICTs) that has enabled the growth of 'collaborative consumption'. While it is indeed undeniable that digital technologies accept enabled new forms of consumption and services, there is however an on-going fence equally to, precisely, what office of this recent phenomenon is actually new. In particular, while this is certainly the nearly widely used term, there has been a lot of criticism of the sharing economy denomination, which is considered by some equally a misnomer, because that bodily sharing seldom happens. Instead, the vast majority of these services do imply fiscal transactions (Eckhardt and Bardhi 2015).

Consequently, at that place accept been attempts to find an advisable denomination for this new phenomenon. Eckhardt and Bardhi (2015), for instance, suggested the designation 'admission economy', because platforms, such as Airbnb, Uber and Blablacar, provide access to spare capacities, whether of physical goods or people (or both, in the case of Uber). However, information technology has been argued, rightfully, that providing 'access' to resources is what businesses accept been doing all forth and, therefore, admission economy is non an accurate description of the new phenomenon.

Indeed, if ane has a thorough look at the various services that are mostly considered as representative of the sharing economy, ane cannot help but detect that at that place is, indeed, nothing really new virtually the services offered. Often, there is fifty-fifty zippo really new about the fashion there are offered (e.thousand. holiday accommodations or taxi rides have been 'rented' through intermediaries earlier). What is really new is by whom these services are offered: consumers. Footnote 18

Equally a matter of fact, a close exam of the key examples of the sharing economy reveals that they all mostly relate to prosumption. And this is what is actually new: Digital technologies have enabled to aggrandize offline (i.e. with concrete appurtenances) the opportunities of prosumption. In this respect, Belk (2014) considers the sharing economy as the offline extension of the online Web two.0 phenomenon. Consequently, it would only seem sensible that the phenomenon usually referred to as sharing economy should in fact be named 'prosumer economy', since generalised prosumption is the defining feature of this new phenomenon.

The various examples of offline prosumption mentioned in this section are summarised in Table 4. In the case of consumer innovation, such as Square Helper, consumers take a leading office in all aspects of the output, also every bit most of the inputs. In this respect, information technology can be noted that digital manufacturing technologies enable to substitute capital (intellectual or physical) for labour. Unlike in the 'old fashioned' user innovation described in 'Prosumption in the pre-digital era' section, user innovators present seldom demand work force in order to innovate (though they may however use it, if they prefer to).

Platform such equally 3D Hubs enable consumers to provide on-demand manufacturing services, in which case they have a leading role in providing the physical capital (i.due east. the printer) and, of course, in manufacturing (they might occasionally have to supply intellectual majuscule to fulfil the service, for instance if the client failed to supply a practiced plenty digital pattern).

Finally, the prosumption framework introduced in 'Towards a prosumption framework' section can exist used to draw contributions to inputs and outputs in the sharing economic system. In that example, manufacturing relates to the production of the service (e.g. renting a room, a auto drive) and distribution relates to the connection betwixt the supplier of the service and the client. Thus, prosumers who supply services every bit a part of the sharing economy play a leading role in providing concrete upper-case letter (their flat, their auto). In some cases, the service involves labour (e.g. driving people) and might also involve intellectual capital (east.g. providing an highly-seasoned clarification of a apartment for Airbnb). With regard to the output, consumers accept a leading role in delivering the service (manufacturing), but only a pocket-size role in distribution, since it is the platform (Airbnb, Uber, etc.) that plays the main part in connecting people.

Overcoming the challenges of leveraging prosumers

Based on the previous department, information technology is quite clear that digital technologies have turned prosumption and user innovation from something that was totally under the firms' command into a phenomenon that tin take place, both online and offline, in total independence from the firms. In fact, nowadays, digital technologies enable about anyone to become an entrepreneur and commencement competing with existing businesses. Consumers have therefore become competitors, and whether they terminate up cooperating or competing with a house depends largely on the firm's strategy.

In such a context, 'hearing the voice of the consumers' has turned from something mainly optional into something cardinal. Because they refused to practise and so, several industries have been heavily disrupted past prosumption (whether 'legal' or not). The recording industry, which was pushing for more expensive college quality physical formats (e.one thousand. DVD-A, SACD), while most consumers wanted cheaper, lower quality music directly distributed online, is a skillful case of that. By not listening to consumers, the industry triggered a pandemic of illegal prosumption ('piracy'), which was just curbed (despite numerous attempts) once adequate offer (e.g. Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music) had appeared (Aguiar and Waldfogel 2015). Unfortunately for the recording manufacture, overlooking (actual or potential) prosumption led to the entry of new competitors that understood much improve the needs of the consumers and took consumers' ability to obtain what they needed past themselves as a starting point for their new business models. Footnote nineteen

Likewise, it tin be argued that the and so-chosen 'uberisation' of the economy is in fact caused by a lack of understanding of consumer needs and past a gross underestimation of the prosumption potential. Indeed, it is articulate that digital technologies have fabricated, through prosumption, most markets contestable. Contestable markets (Baumol 1982) are characterised past a modest number of firms that are forced to operate at near-competitive levels (where profits are close to zero) because of the threat of short-term entrants. This occurs when (1) market place entry and go out costs are very low, (2) at that place are no sunk costs and (three) entrants have access to the same engineering science as incumbents.

Thanks to digital technologies, consumers are often placed in this state of affairs. Unlike a business, they do not need to invest, as they already own the appurtenances (east.yard. automobile, couch or apartment, 3D printer). They have virtually no cost of entry or go out (it takes only a couple of minutes to sign up to Blablacar or Airbnb). Finally, they take now admission to the same engineering science as the 'big boys' (Uber, with Uber Popular, provides everyone with central booking platform, but like professional taxis take; Shapeways enables everyone to 3D print with machines that cost hundreds of thousands of euros). Considering digital technologies brand markets contestable, this renders value capture more challenging, as any endeavour to leverage value to a large extent might trigger the entry of prosumers on the market.

Yet, this is not the simply issue, as there are besides strong implications for user innovation. In the pre-digital era (and, all the same, until fairly recently for physical products), firms were entirely in control of the fate of user innovation. If an innovation suggested by users did not fit the firm'south strategy, it would just exist disregarded, equally it was highly unlikely that the innovator could do anything independently from the firm (especially in the case of a consumer). As was shown in the previous sections, digital technologies have inverse everything: Nowadays, consumer innovators are able to release and diffuse their innovation without any help from the firm.

In the digital realm, a typical example of this is the iOS 'Jailbreak' that has existed most since the early on days of the iOS platform (and despite continuous attempts of Apple to prevent it) and enables users (more often than not consumers) to introduce features and software that Apple tree did not have to include in its operating system (merely, occasionally, decided to include at afterwards stage).

Nowadays, similar phenomena do too take identify in the 'physical' realm. For case, in 2013, Fernando Sosa, a fan of the TV testify 'Game of Thrones', spent a significant corporeality of time designing a smartphone charger dock in the shape of the famous throne of the series. As in the instance of the Square Helper discussed in 'Prosumption goes offline: 3D press and sharing economy' section, Fernando Sosa wanted to lengthened his innovation. After a contact with the right holders' (HBO) lawyers, Sosa asked for an official licence and offered to pay HBO a percentage on sales, which was denied. Footnote 20 While, as per HBO's request, Sosa stopped selling the famed dock, the digital blueprint of a very similar object surfaced very presently after on sharing websites and peer-to-peer networks.

Interestingly, this shows that the marketplace is non but contestable not only with regard to what is produced by the firms only as well with regard to all the potential complements and derivatives that are not. If at that place is a need that is non fulfilled by the firm (due east.g. Game of Thrones merchandising), consumers volition fulfil it themselves, regardless of whether the firm wants it or not. Whereas earlier the digital era, a 'void' in the market place, whether deliberate or not, would remain void, nowadays, it is more than likely that such a void will be filled by prosumption.

Still, the challenges caused past prosumption can exist overcome past embracing the prosumption phenomenon. Every bit mentioned in Rayna and Striukova (2016), Hasbro has adopted a completely reverse strategy to HBO's for its 'My Little Pony' franchise. Instead of attempting to curb prosumption, Hasbro decided to encourage information technology, which provided the opportunity to control it. Realising that consumer fans would eventually pattern, industry and try to distribute objects inspired past the characters of the franchise, Hasbro, instead of blocking them, gave them a platform to do and then.

Hasbro signed a deal with the online 3D press platform Shapeways, which enables fans to upload and sell objects inspired by the My Lilliputian Pony franchise. Footnote 21 Fans can upload any object inspired by the franchise, for as long as it abides some common sense rules (and is really printable), and sell them at a toll of their choice. In render, Hasbro gets a (small) pct of the sales price and controls what is put for sell.

The resulting objects are arguably of very good quality. Footnote 22 By embracing prosumption instead of fighting it, Hasbro has created an ecosystem that enables them to benefit from the creativity and skills of consumers. And, of course, if any particular of those prosumer objects go highly in demand on Shapeways, nix prevents Hasbro from making it a function of its regular product line and mass-manufacture it.

While these are only a couple of examples, at that place is a clear trend towards a greater (potential or actual) prosumption. Yet, in many cases, prosumers still constitute an untapped resource, although many of them are skilled, educated, very much knowledgeable of their needs and of the needs of others, and also have means (or have access to ways) of product (whether pattern, manufacturing or distribution). While some companies have learned to apply 'prosumer power' to their advantage, most do non. Considering of that, they face the take a chance that i day, a priori cooperative consumers get their competitors or that a new entrant that understands how to leverage prosumers wipes these firms out of their own marketplace.

It is thus critical that firms stop considering consumers as a (somewhat) captive herd, but, instead, as coopetitors in a articulation ecosystem. Involving all the participants in the ecosystem and ensuring that the benefits of the ecosystem are 'fairly' shared is certainly a challenge that an increasing number of firms will have to face up in the near time to come.

Conclusion

It is articulate that digital technologies have had a major touch on on prosumption and user innovation. From a situation where prosumption and user innovation were (generally) initiated past firms and carried out under their total control, digital technologies have progressively made prosumption and consumer innovation ubiquitous and unavoidable.

Yet, prosumption tin and does take many forms and each unlike form comes with different challenges for the firms. It was therefore necessary to understand precisely the nature of each form of prosumption. The framework introduced in 'Towards a prosumption framework' section enables to practise so, as illustrated past its awarding to multiple case studies throughout the commodity.

1 of the insights provided by the utilize of this framework is that while digital technologies have enabled consumers to be leading with regard to any aspect, whether input (labour, intellectual capital, concrete capital) or output (design, manufacturing, distribution), of the product procedure, the actual form of prosumption that prevails on the market oftentimes has a rather minimal involvement of the prosumer (e.m. music is not distributed on peer-to-peer networks, prosumer withal needs a visitor like Blablacar to intermediate). In fact, it is quite likely that in many situations, total-scale prosumption is neither achievable nor desirable.

Still, prosumption has become a reality and most successful business models integrate, at least to some extent, some form of prosumption. As discussed in 'Overcoming the challenges of leveraging prosumers' section, regardless of the extent to which information technology happens, prosumption is a force to reckon with, as it not only makes most consumer markets contestable merely also enables consumers to fill in gaps left past firms in the market.

For firms, involving prosumers has not but go an obligation, but it tin likewise be a significant source of competitive advantage. Nonetheless, at that place is a fine line between prosumption benefiting the firm and prosumption undermining the firm. A line that, furthermore, moves over time! As discussed in 'Overcoming the challenges of leveraging prosumers' section, there is undoubtedly a shift needed towards ecosystem management, where consumers are no longer seen as a (relatively) captive heard merely as legitimate competitors.

Whether actual or potential, the importance and the effect of prosumption in the economy have considerably increased over the past decades. With prosumption reaching the realm of concrete objects and services, one could debate that the industry disruptions that take been observed online are near to reach the unabridged economic system. Hence, the question is: are nosotros moving abroad from a 'digital economic system' towards a prosumer economy?

Notes

-

See, for instance, the case of the 'Game of Thrones' smartphone dock, p. 25.

-

Run into, for case, the example of the Square Helper, p. 17.

-

At the time, equally its French root consumer (i.e., 'burn') implies, it referred to someone who spent recklessly and wasted resource.

-

As opposed, for instance, to the work on a medieval subcontract, where people would first produce for themselves and then trade what they did not eat in order to obtain goods or services they did non produce.

-

In contrast, there was a keener interest during the 1980s and 19990s in the role played by clients—more often than not in a business to business concern setting—in service and innovation processes.

-

Though, as will be discussed in the following sections, additive manufacturing/3D Printing technologies enable user innovators to mechanise the prototyping stage.

-

It could likewise be argued that all iii types of input are always involved. For instance, music downloads crave some labour (to click on the 'download' button) too as some intellectual capital letter (to exist able to choose which track to download). Likewise, while all necessary tools are provided with Ikea flat packed furniture, scissors (i.due east. concrete capital) might be required to open the packaging, besides while a detailed transmission is supplied, some elements of intellectual capital (e.1000., beingness able to read) are besides needed. However, in those cases, it is clear that quantity of such inputs used is negligible.

-

In dissimilarity, User Innovation carried out by businesses (due east.g. the traditional example of scientific instruments used by universities and R&D labs) is not prosumption.

-

Publishing a picture online alone would crave using a picture editing software (to compress the flick), an HTML editor to write the code of the webpage on which the picture show would be displayed, and an FTP client to upload the files to a remote web server.

-

Every bit a comparison, 15 years later and despite a heavy worldwide advertisement campaign, Apple tree Music just reached xi million users during its initial three-calendar month free trial (Byford 2015). Spotify, the music streaming marketplace leader, had equally of January 2015 60 million users, including 15 1000000 paying users (https://news.spotify.com/us/2015/01/12/fifteen-million-subscribers/).

-

For this particular example, the tabular array displays 'Minor' for labour because of the original and repetitive chore of 'ripping' (importing in the reckoner and converting to MP3) CDs and vinyls.

-

Airbnb is a platform that enables people to allow (often sublet, in the instance of a flat) a couch, a room in their home, or fifty-fifty the whole apartment).

-

Blablacar is a platform that connects drivers and passengers willing to travel together betwixt cities and share the cost of the journey.

-

Uber is a mobile app that enables consumers with smartphones to submit a trip request that is then routed to Uber drivers who use their ain car.

-

Uber, in many countries, offers different types of services: taxi rides operated past professionals (e.chiliad., Uber X) and transportation services offered by non-professional individuals (due east.g., Uber Popular). It is the latter that is mostly idea as being part of the 'sharing economic system'.

-

Hasbro also offers through Shapeways licences for a couple of other of its franchises, such equally DragonVale, Dungeons&Dragons, GIJoe, Monopoly, Scrabble or Transformers. http://world wide web.shapeways.com/engage/superfanart

References

-

Aguiar, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2015). Streaming reaches inundation stage: does Spotify stimulate or depress music sales? Institute for Prospective Technological Studies Digital Economy Working Paper 2015/05, European Commission Joint Research Center.

-

Baumol, W. J. (1982). Contestable markets: an insurgence in the theory of industry construction. American Economic Review, 72(1), one–xv.

-

Belk, R. (2014). You are what y'all tin can access: sharing and collaborative consumption online. Periodical of Business concern Research, 67(8), 1595–1600.

-

Byford, S. (2015). Apple Music has a third as many paying subscribers as Spotify. The Verge. Published 20 October 2015 (Retrieved 28 October 2015). http://www.theverge.com/2015/10/20/9572667/apple tree-music-subscriber-count-number-paid.

-

Eckhardt, 1000. M. and Bardhi, F. (2015). The sharing economy isn't about sharing at all. Harvard Business Review. Published 28 January 2015 (Retrieved 29 October 2015). https://hbr.org/2015/01/the-sharing-economic system-isnt-near-sharing-at-all.

-

Galbraith, J. K. (1958). The Flush Lodge. Houghton Mifflin.

-

Galbraith, J. K. (1967). The New Industrial Land. Princeton University Press.

-

Gowan, Grand. (2012). Requiem for Napster. PC World. Published 18 May 2002 (Retrieved 28 October 2015). http://www.pcworld.idg.com.au/article/22380/requiem_napster/.

-

Hamari, J., Sjöklint, 1000., & Ukkonen, A. (2015). The sharing economy: why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Data Science and Engineering. doi:ten.1002/asi.23552.

-

Kotler, P. (1986). The prosumer movement: a new challenge for marketers. Advances in Consumer Research, 13(1), 510–513.

-

Lüthje, C., Herstatt, C., & Von Hippel, Due east. (2005). User-innovators and "local" data: the case of mount biking. Enquiry Policy, 34(6), 951–965.

-

Martin, S. (2013). Square Helper: designed and mass manufactured in a home function with a MakerBot. SolidSmack. Published 18 January 2013 (Retrieved 29 October 2015). http://www.solidsmack.com/culture/square-helper-designed-and-manufactured-in-a-domicile-office-with-a-makerbot/.

-

Matsuyama, K. (2002). The ascension of mass consumption societies. Journal of Political Economy, 110(5), 1035–1070.

-

Rayna, T. (2008). Understanding the challenges of the digital economic system: the nature of digital goods. Communications & Strategies, 71, thirteen–26.

-

Rayna, T., & Striukova, L. (2010). Large-calibration open innovation: open source vs. patent pools. International Journal of Technology Management, 52(iii/4), 477–496.

-

Rayna, T., & Striukova, L. (2015). Open innovation 2.0. Is co-cosmos the ultimate challenge? International Periodical of Technology Direction, 69(ane), 38–53.

-

Rayna, T., & Striukova, L. (2016). From rapid prototyping to home fabrication: how 3D Press is changing business model innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 102, 214–224.

-

Rayna, T., Striukova, Fifty., & Darlington, J. (2015). Co-creation and user innovation: the role of online 3D printing platforms. Journal of Engineering science and Technology Management, 37, xc–102.

-

Ritzer, M., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, consumption, prosumption: the nature of capitalism in the age of the digital 'prosumer'. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(1), xiii–36.

-

Tapscott, D., & Williams, A. D. (2006). Wikinomics: how mass collaboration changes everything. New York: Portfolio.

-

Toffler, A. (1981). The third wave. New York: Runted Books.

-

von Hippel, E. (1976). The dominant role of users in the scientific instrument innovation process. Enquiry Policy, 5(3), 212–239.

-

von Hippel, Eastward. (1977). Transferring process equipment innovations from user-innovators to equipment manufacturing firms. R&D Direction, 8(1), xiii–22.

-

von Hippel, East. (1978). A customer-active epitome for industrial product idea generation. Research Policy, vii(3), 240–266.

-

von Hippel, E. (1986). Lead users: a source of novel production concepts. Management Science, 32(seven), 791–805.

-

Zwass, V. (2010). Co-creation: toward a taxonomy and an integrated research perspective. International Periodical of Electronic Commerce, 15(1), 11–48.

Author data

Affiliations

Respective author

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilize, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rayna, T., Striukova, Fifty. Involving Consumers: The Role of Digital Technologies in Promoting 'Prosumption' and User Innovation. J Knowl Econ 12, 218–237 (2021). https://doi.org/x.1007/s13132-016-0390-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-016-0390-8

Keywords

- Prosumption

- User innovation

- Digital technologies

- Sharing economy

- 3D printing

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13132-016-0390-8

0 Response to "In the Near Future Do You See Yourself as a Consumer Producer or Prosumer of Digital Arts"

Post a Comment